Photographer Edouard Boubat (1923-1999) is a poet with a camera. His work is part of the great tradition of French photography that includes such masters as Brassai, Bresson and Doisneau. From his pictures of people in post-war France to photos he took late in his life in the nineties there is a continuity in his gentle attitude that bridges both time and place.

Photographer Edouard Boubat (1923-1999) is a poet with a camera. His work is part of the great tradition of French photography that includes such masters as Brassai, Bresson and Doisneau. From his pictures of people in post-war France to photos he took late in his life in the nineties there is a continuity in his gentle attitude that bridges both time and place.

Boubat, who worked as a freelance photojournalist and on contract for the magazine “Réalités” in the 1950s and 1960s sought to make photos that were a celebration of life. The French writer Jacques Prévert once called him a “Peace Correspondent.”

This winter the Maison Europpenne de la Photographie features a 150-photo retrospective of Boubat’s work “Révélations” (until March 30). We take the opportunity to republish a Parisvoice interview with Boubat that took place February, 1988.

B.B: The photographer Gary Winogrand once said that he took photos because he wanted to see what things look like when they are photographed. Why do you take photos?

E.B: I started taking photos because I was interested in art, beauty and drawing. But unlike many photographers I never wanted to be a painter. I am a photographer by nature.

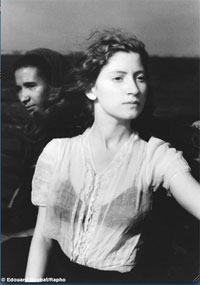

My first contact with photography was during the war when I was doing “photogravure” work. When I started making pictures after the war I didn’t know anything about what was going on in photography. I had never studied it. I didn’t have any photo books or people to copy. So I was able to start completely free, very virgin-like. It was this freshness which permitted me to make my first photos such as Lella in 1947.

B.B: Your photos have been described as being romantic…

E.B: They are not romantic. They are humanistic. I don’t like categories, but I am usually included with photographers who are interested in photographing people…humanity, with such people as Doisneau, Bresson or the American photographer Eugene Smith.

B.B: There is a meditative quality to your work…

E.B: I prefer that word to describe my photography. When I take a picture I don’t think. In the precise second I take the picture my mind is blank. Later it can be analyzed and one might say that it is meditative or not, but while the process of making the picture is going on…blank..

B.B: You have been photographing people for some forty years. Has it given you any special insight into human nature?

E.B: When I see people I also see the spirit of goodness, kindness and love. Of course when I am taking a picture I’m not thinking about those things. I don’t think “Now I’m going to take apicture of love.” But sometimes I catch those things in my photos.

B.B: Your photos have a joie de vivre quality to them, or maybe it could be called a joie de photo…

E.B: Yes, it’s true, but I hasten to add that I well realize the world can be very hard. Very bad. When Van Gogh painted his flowers he knew very well about sadness, but through these flowers one can see something else, a kind of transcendence. It’s not necessary to take pictures of bad things or war to know that they exist.

My photos are more than the subjects in them. There is a clear subject, true, but it is transcended. The writer Borges once said, “there should be more to a writer’s work than just what the writer thinks.”

The same is true with photography. It must be much more than what the photographer is thinking. It has to have a transcending quality to it.

B.B: Is that quality meaning?

E.B: No. Even when a reporter takes a picture he has no meaning. But later people put meaning to that photo with a layout or with captions. The same photo can say many different things.

B.B: So, your photos are more art than documents.

E.B: I don’t believe in photographic objectivity because when you put ten photographers at the same time in the same room you get ten different pictures. Objectivity is very changeable.

B.B: The humanistic feel of your work is at odds with the postmodern aggressivity that pervades today’s media.

E.B: Yes, we are constantly aggressed by visual images. But I don’t want to add to that. We are living in a declining civilization. It’s like the Roman Empire with everything collapsing.

B.B: I noticed that the photos you took in the U.S. have a harder feel to them than the ones you made here in France. Are you conscious of shooting differently there?

E.B: Wherever I travel I get different feelings. Although I don’t believe in photographic objectivity, I do believe in what I could call ‘photographic atmosphere’ or ‘ambiance.’ I catch the atmosphere of places where I am traveling. I think photography is special in how it captures atmosphere. In fact atmosphere is more important than what you are thinking when you make the picture. Spontaneity is very important in photography.

B.B: I have always loved your photo “Lella, 1947” and wondered whether you set it up to get that Mona Lisa effect.

E.B: That was a long time ago, and it was my first love. We were 20 then. I made a book last year with only photos of her. But it’s very hard for me to analyze my first work.

B.B: Do you do much commercial work?

E.B: No. Very seldom. It’s a miracle, but I can live selling my prints. I do assignments sometimes for newspapers and I do a lot of portraits. Sometimes I feel that I am living like a “oiseau sur la branche”

B.B: Among your photos do you have one that you prefer over the others?

E.B: My favorite photo is always the last one that I took.

Photo caption: Lella, France 1947, photo: Edouard Boubat-Rapho