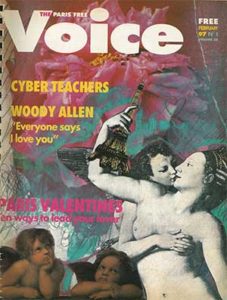

We knew he could play the clarinet, write and direct like nobody’s business, act a mean nebbish, ignite misguided controversy and woo quirky and/or much younger women. But what most people – including the nation’s professional film critics and his Paris publicist – never suspected about Woody Allen is: He speaks French.

We knew he could play the clarinet, write and direct like nobody’s business, act a mean nebbish, ignite misguided controversy and woo quirky and/or much younger women. But what most people – including the nation’s professional film critics and his Paris publicist – never suspected about Woody Allen is: He speaks French.

By his own admission, Allen barely understands the tongue of Molière, but he speaks it remarkably well, as he demonstrated throughout a stay at the Ritz right before Christmas. Allen press conferences, anywhere on earth, tend to be scarcer than for female chickens, but Woody, who in addition to being a genius is no dummy, has apparently decided to try to “sell” his latest film, the fluffy, stupendously entertaining musical comedy “Everyone Says I Love You.”

My 91-year-old landlady once remarked that she’s suspicious of promotional tactics, since in her day advertising wasn’t really necessary. (“Huh?” replies her eloquent tenant. “Mais, oui,” says the nonagenarian. “Everybody already knew what the quality brands were. Only a possibly inferior upstart would feel the need to advertise.”)

Woody Allen is as venerable a name as Cristofle or Veuve Clicquot in my book. He’s written and directed 27 films in three decades, appearing in nearly every one. Despite Woody’s concession to promotional fervor, the no-need-to-advertise rule holds truer in France than in any other market. When Allen’s longtime studio, Orion Pictures, was mired in financial woes, his German Expressionist spoof “Shadows and Fog” was released in Gaul sans fanfare months before it hit screens elsewhere. In France – where “Manhattan Murder Mystery” played for months on end and “Alice” earned over half its total box office receipts – all you have to do is put an Allen film in theaters and people show up.

“For reasons that remain mysterious to me,” Allen commented, “my films are appreciated more in Europe – and in France in particular – than they are back in the U.S. Could it be that the subtitles over here are incredibly brilliant?”

As moviegoers will discover February 12, Woody’s tuneful opus investigates an upper East Side household in which liberal Democrats Alan Alda and Goldie Hawn preside over an assortment of children, stepchildren, distinguished elders and a Bavarian housekeeper whose stern worldview prompts the funniest line of dialogue ever to be written on the subject of pasta. The token son among saucy daughters is a conservative Republican, which leads to one of the cleverest explanations for right-leaning politics ever conceived.

Those who haven’t bothered to notice that Allen is to genre experimentation what Diderot is to l’Encyclopédie often criticize the prolific comedian for reworking the same themes and reprobing the rarefied air around privileged New Yorkers and their shrinks. “I live in an upscale neighborhood and I think rich people are funny,” Allen explained in a cozy salon at César Ritz’s humble holstelry on the Place Vendôme, “because they have a lot of money and they still have a lot of problems.”

Woody plays Joe, an American writer who is divorced from Hawn and living in Paris. (The geographical tip-off is a scene of Allen with a baguette under his arm heading toward the Conciergerie.) Allen, who admits to loving “traffic, noise and pollution” and despising the countryside, says: “I wanted to make a movie in my three favorite cities, so I wrote a story that takes place in New York, Paris and Venice.” Joe’s latest romantic failure prompts a trip to New York, where his musings on the advantages of taking the Concorde if one’s in a hurry to commit suicide in France would bring a smile even to the Grim Reaper’s lips, if he had lips. And the jubilatory memento mori scene in a funeral parlor would bring a jig to his feet, had Death feet.

Does Allen ponder how he’ll be thought of when he’s gone? “I fear death, of course,” Allen replies, “but I don’t think of posterity for my films because I’ll be dead and it won’t matter. I’d like to be appreciated now, while I’m alive. After, it’s not important. For someone like Shakespeare, what difference does it make? He’s dead.”

Whether it’s a calypso for the deceased or the briefest but most astute précis yet issued on rap, in “Everyone…” Allen embellishes his exploration of music as an integral storytelling tool last in evidence in the wacky Greek chorus lyrics of “Mighty Aphrodite”. Since the songs in “Everyone…” are all pre-existing, could the next step be a “real” written-from-scratch musical?

“I would very much like to do what’s known in America as a ‘book show’ with original music and lyrics, but it’s difficult because I’d need the kind of composer who works in the idiom of another era,” Allen admits. “What I want to do wouldn’t fit the rock melodies that have predominated since the 1960s – simple 32 bar songs were more conducive to supplementing the narrative.” Allen says he loved Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers movies as a kid – “The stories were trivial but the music and dancing were fantastic” – and cites the color musicals of Vincente Minnelli and Stanley Donen in the 1950s as “possibly America’s best films.”

One of the Paris production numbers in “Everyone Says I Love You” involves a choreographed cluster of Groucho clones singing “Hooray for Captain Spaulding” translated into French. In addition to proving that there is no French rhyme for “schnorrer,” the passage illustrates Allen’s obvious love for the Marx Bros.

“I think the Marx Bros are the greatest American film comedians of all time,” he says.”Their humor is utterly surreal and, at the same time, deeply profound. It was my privilege to know Groucho toward the end of his life. What’s more, and I’m quite serious about this, my own mother is a dead ringer for Groucho.”