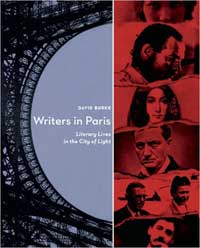

Literary detective David Burke explores the most creative quartiers of the City of Light — the Latin Quarter and the Marais, raffish Montmartre, “Lost Generation” Montparnasse, and others – and tracks down the haunts of dozens of the world’s finest and most colorful writers.

Literary detective David Burke explores the most creative quartiers of the City of Light — the Latin Quarter and the Marais, raffish Montmartre, “Lost Generation” Montparnasse, and others – and tracks down the haunts of dozens of the world’s finest and most colorful writers.

From native Parisians such as Molière and Marcel Proust to expatriates like Henry Miller and Samuel Beckett, Writers in Paris follows their artistic struggles and miraculous breakthroughs, along with the splendors and miseries of their invariably complicated personal lives. Burke also pinpoints key places in the lives of fictional characters, including Gargantua’s ribald visit to the towers of Notre Dame and Vladimir and Estragon’s wobbly first step onto the stage of an obscure little Left Bank theater.

With maps, descriptions, and more than one hundred photographs, Writers in Paris gives a fresh, fascinating way of looking at the city and its unparalleled role in literature.

Here is an excerpt from the book on writers who congregated around Place Vendôme

The epitome of late-seventeenth-century urban development, Place Vendôme was designed by Jules Hardouin-Mansart in 1686. The splendid façades on the octagonal square were built right away, but it took forty years for all the buildings behind them to be completed. Most were private residences of bankers and financial speculators, most notoriously John Law, the bursting of whose “Mississippi Bubble” in the 1720s ruined countless investors. The buildings are now occupied by government offices, banks, upscale boutiques, and the Ritz.

THE RITZ

Now a synonym for luxury and high living (“puttin’ on the ritz,”), the word originated as a family name, that of César Ritz, the Swiss hotelier who opened his establishment on the Place Vendôme in 1898. He guaranteed the hotel’s success by hiring Auguste Escoffier, a man renowned for his haute cuisine, as the chef. The Ritz, at No.15, was home to the duchesse de Gramont, the Maréchal de Lautrec, and Voltaire’s friend the Marquis de Valette, among others.

PROUST

The Ritz was Proust’s favorite place for a night on the town in his later years. He even kept a suite, preserved in its Louis XV style. Proust would arrive around midnight, roam the lobby in his fur-lined overcoat, observe people in the public rooms, get together with friends, and soak up the gossip from the omniscient maître d’hôtel Olivier Dabescat, the model for his counterpart Aimé at the Grand Hôtel de Balbec in In Search of Lost Time. He also flirted with a young waiter named Henri Rochat, who moved into his apartment on Rue Hamelin. Proust loved the iced beer introduced by the hotel and famously sent his driver Odilon to fetch some as he lay on his death bed.

FITZGERALD

Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald spent more time at the Ritz bar than was good for them during their five stays in Paris between 1924 and 1931, when Zelda’s mental collapse put her in a sanitarium. But Fitzgerald put the Ritz to superb fictional use in his novel Tender is the Night and in his story “Babylon Revisited,” published in 1931. In it, Charlie Wales has returned to Paris after a year and a half of sobriety to gain custody of his daughter Honoria, who is in the care of his dour sister-in-law Marion, the girl’s legal guardian, since his wife’s death. He finds the mood of the city very different from what it had been before the Crash, when he was one of those Americans on the années folles binge. Now, “the stillness in the Ritz bar was strange and portentous. It was not an American bar any more — he felt polite in it, and not as if he owned it. It had gone back into France.”

HEMINGWAY

During the final days of the Occupation in August 1944, Ernest Hemingway and his band of irregulars “liberated” the wine cellar of the Ritz. That bit of history, along with the grand cru publicity value of the Hemingway name, got him a bar named in his honor.

Though the Ritz does not appear in Hemingway’s works from the 1920s, he wrote about the period in his memoir A Moveable Feast, a quarter of which is devoted to trashing the memory of his long-dead friend Fitzgerald, the first person to invite him to the Ritz when he was too poor to afford it:

“Many years later at the Ritz bar, long after the end of World War II, Georges, who is the bar chief now and was a chasseur when Scott lived in Paris, asked me, “Papa, who was this Monsieur Fitzgerald that everyone asks me about?”

Georges puzzles over the mystery of why he remembers Hemingway, who was too poor to come often, but can’t remember Fitzgerald, who was said to be a regular. The scene ends with him telling Hemingway, “You write about him as you remember him, and then if he came here, I will remember him.”

“We will see,” Papa responds.

OBELISK PRESS

Englishman Jack Kahane’s Obelisk Press became famous in the 1930s as a publisher of English-language books too hot for companies in Britain and America to handle, most notably Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer, published by Obelisk in 1934. Other steamy titles included Miller’s Black Spring and Tropic of Capricorn, Anaïs Nin’s The House of Incest, Lawrence Durrell’s The Black Book, and reprints of Radclyffe Hall’s lesbian tearjerker The Well of Loneliness and Frank Harris’s four mind-numbing volumes of sexual confessions, My Life and Loves.

But Kahane also craved literary respectability. He published deluxe editions of his idol James Joyce’s Pomes Penyeach and Haveth Childers Everywhere, and a fragment from Work in Progress (Finnegans Wake), as well as Richard Aldington’s novel Death of a Hero and Cyril Connolly’s Rock Pool.

Obelisk’s address, No. 16 place Vendôme, also testifies to his yearning for respectability: It was quite literally a front. The entrance from the stylish square opened into a long, narrow corridor leading to a little room in the back.

HARRY’S NEW YORK BAR

Just around the corner from the Place Vendôme via the Rue de la Paix is Harry’s New York Bar at No. 5 rue Daunou, or “SANK ROO DOE NOO,” as a sign in the window says. Opened by the American jockey Ted Sloan in 1911, the bar did a land-office business with American army officers and ambulance drivers during World War I, but when Sloan ran into financial difficulty in 1923 he sold it to bartender Harry MacElhone, a New Yorker. Hemingway claimed that Harry invented the Bloody Mary for him in the 1940s, supposedly because the tomato juice, Worcestershire and Tabasco sauces would hide the scent of alcohol from his girlfriend Mary Welsh. Actually, the drink was invented around 1920, most likely at this bar, but probably not by Harry. He certainly was a friend of Hemingway, however, starting in the 1920s, seconding him at boxing matches in Montmartre and holing up in the bar afterwards to rehash the events.

Another of the establishment’s claims to fame: George Gershwin composed An American in Paris on the piano downstairs during his long stay in Paris in 1928.

Among the many other writers who warmed to the bar’s clubby male atmosphere were Fitzgerald, Sinclair Lewis, Noël Coward, Ian Fleming, and, surprisingly, Jean-Paul Sartre, who discovered bourbon and hot dogs here.

Writers In Paris: Literary Lives in the City of Light by David Burke (Counterpoint )