What turns a pop music star into a legend? A decade or two of hit songs? A distinctive vocal style? An outrageous hairstyle? Whatever the criteria may be, few performers pass the threshold from star to legend on talent alone, and fewer still are women.

What turns a pop music star into a legend? A decade or two of hit songs? A distinctive vocal style? An outrageous hairstyle? Whatever the criteria may be, few performers pass the threshold from star to legend on talent alone, and fewer still are women.

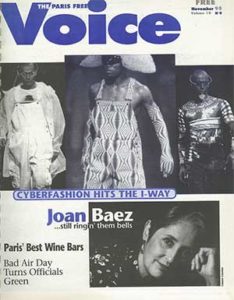

Joan Baez is one of a select group of female musicians popular enough to enjoy instant name recognition by any American over 30. (When Forrest Gump’s girlfriend, Jenny, pulls her hair back in a ponytail and picks up a guitar, it is the Queen of Folk that she pays tribute to.) And yet, unlike male colleagues who often built their reputations around off- and onstage high jinks, Baez is best remembered for her simplicity and untiring political idealism. Wherever she performs, large crowds still gather to hear her bell-like soprano and the traditional folk music repertoire that is unmistakably hers. Her raven hair has turned silver now, and both her political and musical voices have mellowed, yet the 54-year-old songstress has never let dust gather on her acoustic guitar. During a recent visit to Paris to promote her concerts November 2-3 at the Bataclan and her new album, “Ring Them Bells,” she spoke candidly about her 37-year career.

FV: How often do you come to Paris?

JB: I started doing concerts here in 1966 and came regularly for the next few years. In the ’80s I would come to France but bypass Paris for Normandy. I had met a count while I was doing relief work in Cambodia and it turned out that he owned this 13th century castle. Entering an environment like that was like living in a fairy tale, especially for an American.

FV: I have the impression that you don’t consider yourself a typical American.

JB: Well, I’ve never been a patriot, if that’s what you mean. A lot of Americans hated me for that but they didn’t know I felt the same way about anyplace. My loyalties have never been with the land or the flag – that’s what has made a mess of things so many times.

FV: Do you feel like an outsider in the United States?

JB: I started feeling like an outsider in general since I kept changing schools as a child – and then coming back from Baghdad; I spent a year there when I was ten. Even to this day, I’ll go to Tunisia and hear some Arab music and out of the blue I’ll feel that this is “home.”

FV: Let’s talk a bit about the new album. What kind of sound were you looking for?

JB: Well, I wanted this record to sound fresh. At my stage of the game, that’s the most important thing. You can’t take Leonard Cohen’s “Suzanne” and perform it in the same old way. It has to have some element that compels you to listen again and again, and not just for reasons of nostalgia. I also wanted to do some of the classics for the kids who weren’t there back then.

FV: You have a lot of guest artists [on the album], women who are half your age. How did it feel working on stage with them?

JB: Wonderful. It’s a kind of mutual admiration club when we get up there. We share the same musical roots and they feel they are paying homage to that. On my part, I am outspokenly grateful to artists like Mary Chapin Carpenter or the Indigo Girls for the loan of their younger audience. The numbers worked so well, we started inviting other women songwriters.

FV: And yet you only include one song that you wrote yourself.

JB: I told my manager that I didn’t want to write songs anymore. I don’t want to pretend I’m on the cutting edge of the women’s songwriting scene – I’m not. Once in a while a song comes out of me that’s wonderful, but if I force myself to wedge things into a structure, I just go blank. As a songwriter I felt that I was swimming upstream – fighting to do something that wasn’t my primary gift. “Diamonds and Rust” came up on its own. So did “Speaking of Dreams.” If something like that comes up again, I’ll be happy to sit down and structure it.

FV: Do you recall what was going through your mind when you wrote “Diamonds and Rust”?

JB: I remember that I used to have a little studio apartment in Santa Monica, which overlooked the ocean. I sat there one evening strumming my guitar. The tune seemed to be coming along fine, but I was having problems with the words. I had wanted to write a song about Vietnam veterans and somehow this love song came out in its place.

FV: Does the title of the album, “Ring Them Bells,” have any significance?

JB: Not really. That was just the name of the song that Mary Black wanted to do. The editor happened to like the title and used it for the album.

FV: You mean you’re not ringing the bells for any political causes?

JB: Not anymore. If “Ring Them Bells” means anything, it would be on a personal level. About six years ago, I was in the process of making “Speaking of Dreams.” I felt as though an alarm had gone off in the middle of the night. I woke up suddenly and thought, “Why am I making this album? Nobody’s gonna hear it except my mother and a few friends.” I had no machinery behind me to get the record heard and it took me a long time to realize that I had to make that happen if I wanted to be heard – and I do want to be heard.

FV: So, you haven’t been involved in political issues?

JB: I actually had to turn off the TV because it’s so gut-wrenching to watch what’s going on in Bosnia and not be able to do anything about it. I had to pull away from things that came so quickly and naturally to me and found that, in a way, my greatest fight has been to allow myself to be an artist. It’s been good for me because being a political activist had been my safest identity and I needed to break that up.

FV: While we’re talking about current issues, how do you feel about France’s decision to test nuclear weapons in the South Pacific?

JB: It’s so bizarre and, of course, I think it’s loathsome. I don’t think it’s helping things move forward in the world and I’m glad to see that there’s such a reaction against it. It looks to me like a big sort of ego tantrum. Why else do you do that kind of thing now?

FV: Are young people any different today than they were 30 years ago? Are they any more socially aware or politically involved?

JB: Well, we certainly went through a period of tremendous apathy, but I don’t think that lasts forever and I think the vacuum that we’ve lived in for a while may be causing some of the reaction against it. This time around, the awareness and the concern seems to be less political and more spiritual and has more to do with environmental issues. I’m not an expert on it. I haven’t been singing on college campuses, but my son is 25 and his interests are in drumming, healing, shamanism and American Indians and he reacts with great disdain to the great vacuum, to the yuppies and their “information highway.”

FV: People identify you so strongly with the anti-war [and] civil rights movements of the 1960s. Is that ever a problem?

JB: I had this huge reputation in France for that kind of thing. I had this interview yesterday with a French journalist. He couldn’t get out of that time period. I finally put my hand on this man’s hand and said, “I don’t want to talk about this anymore. It’s boring me to death.” I said it in French because when I’m upset my French is pristine.

FV: Do you think there’s any ageism in the music business?

JB: No. If you do something fresh when you’re 85, people will listen to it. Anyway, physical aging isn’t the problem. I know, myself, that I’ve made age jokes in concerts when I felt stale – all self-deprecating stuff – and that was because I didn’t feel good. I was starting to feel old and the years had nothing to do with it. I met Julio Iglesias a few years ago and he started carrying on. “Ah, I look in the mirror and I used to be so beautiful. I used to get all the girls and now I’m getting old.” And I said, “Julio, it’s all up here. I have a bright idea. Go do something for somebody else – you have all that money and all that talent. Quit thinking about yourself.” That went over like a rock! He never talked to me again!

FV: You’ve done a lot as a civil rights activist. What was your greatest accomplishment?

JB: It was probably back in 1963 [when I integrated] an all black school in Birmingham, Alabama. I remember being so frightened. The feeling around me was just electric. I had been staying with Martin Luther King, at a local motel, which, by the way, was bombed later that day. The black man from the movement who drove me across town was driving so fast. I was scared to death. When we finally tumbled out of the car, I saw white people walking across the lawn. The driver said it was the first time he had seen them there. I thought I’d be singing to blacks but they were all in town getting themselves arrested. Black people didn’t even know who I was!

FV: You were the first person to sing those Appalachian folk songs and suddenly you found that there was such a market. Did that surprise you?

JB: I had nothing to compare it with. I was just 17 years old when I moved to Cambridge. I had no ambitions whatsoever. I saw the coffee shop scene and fell in love with it. I started to sing and play the guitar and it was like putting on a glove. It fit perfectly. I happen to have an enormous gift that found its place in those coffee shops and at the same time it was the beginning of the folk boom. It was just a series of miracles, and I was lucky enough to be there.