For the 9/11 anniversary we are re-running a commentary written by Parisvoice’s David Applefield on how this event was experienced by American expats in Paris at that time. The edition with these observations appeared two weeks after 9/11.

For the 9/11 anniversary we are re-running a commentary written by Parisvoice’s David Applefield on how this event was experienced by American expats in Paris at that time. The edition with these observations appeared two weeks after 9/11.

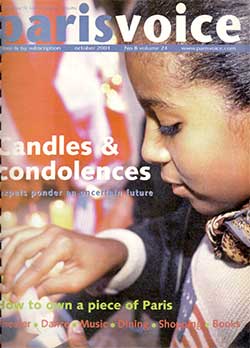

Candles and Condolences… For Americans in Paris the existential task of reflecting on our own identity is one that we are used to already. Almost daily, we are reminded that there are ways — other than our own — of looking at problems, of working, talking, understanding history, or doing almost everything. With the horrendous, live images of our boldest symbols crumbling (in nightmarish repetition) before our screen-abused eyes, being an American in Paris throughout this extended moment of treachery has been an experience drastically different to being an American at “home.”

We test this truth in every long-distance call we conduct. Graciously, we’ve been showered with genuine expressions of sympathy and solidarity from non-American friends, colleagues and neighbors, many of whom we might otherwise have spoken to rarely or with whom the daily cloisson of reserved Parisian behavior remained a barrier. Following the initial shock of disbelief, my first tears were neither in front of a CNN report nor upon hearing the voice of my brother from his New York office saying that he was safe. I choked up, though, with emotion when my Algerian butcher in Montreuil, the guy whom I’ve known only for his lamb chops and sprigs of mint leaves, looked at me with the saddest eyes on earth and said “Je suis vraiment desolé, mon ami. ” I knew then that I was directly connected to the devastation in southern Manhattan, and that the planet’s geo-political fragility would play itself out on every street corner of every town from here on in.

Thinking back to all those reports of innocent throats being slashed by fanatics in my butcher’s homeland, how sorry I am now that I never expressed my sorrow. And the 500 Angolan civilians slaughtered on a train just days before the suicide skyjackings, how sorry I am for those people too. And where on earth were my heart and mind during the ten days when 800,000 Rwandans were hacked to death with machetes for no other reason than their ethnicity? How extraordinary it is that the Slaves and Iraqis in Paris continue to smile and extend their hands.

The gregarious Congolese man at the Total service station around the corner watched his entire city of Brazzaville be crushed. These people have known what we are just learning, and their handshakes and “Comment ça va?” are laced with this knowledge that little people everywhere are crushed not only by highjackers but by the machines of state terror. With each hour on the television, with each new telephone call, and each new article in the numerous publications distributed each morning, our perceptions shift. An American neighbor here in Paris tells me that her family reports of candle vigils in Seattle in front of a local Mosque. We have to protect the innocent, they chant. An African friend calls from Nigeria to check that my family is okay — I’m the only American he knows. Every American in Paris that I know has had a score of concerned calls.

These acts of kindness bring us closer to a consensus: there is an abundance of good will and love in the world, and yet a fear that our country may have been provoked into spoiling the future as we attempt to save it. Stateside, the focus remains on the mourning and the revenge, as if evil wore a uniform and commanded a county, while here dialogue is shifting to the dangers of a cause, and the threat of an oversimplified and muscular response.

My family in Plymouth, Massachusetts tells me that a local pizza parlor owned by an Iranian has been burned down. Sikhs, mistaken for Arabs, have been attacked. The rhetoric intensifies daily and the sadness that has slid into anger now takes on the cold rationality of reactive plans. Our laws are being adjusted to fit acts of reprisal, our personal freedoms are being trimmed to accommodate intelligence requirements, our immigration policies are being re-struck and our collective energy focuses on a new ism: the irradication of terror. We skid from the humility of loss to the industrial bravado of revenge. We sense the shifting of sands, the partitioning of sensibilities, the world taking sides.

As individuals, we must help our leaders by voicing a whole host of opinions that reflect wisdom and experience. The American living overseas is particularly well placed to help in this way. In this instance, we’ve been spared the immediacy of falling concrete and shattered glass, yet we’re sitting on the front lines of the future. Here in Paris, half-way to the Middle East, at the heart of an expanded Europe, on the plaque tournante toward Africa…

We’ve been loved and criticized for a while. But we’re foreigners, even if we are respected and privileged ones. We need to share what we know with other Americans, for whom the diversity of the world is an Iranian-owned pizza shop in Plymouth, Massachusetts, or an olive-toned man at a bus-stop in Texas. We are closer to the non-American world, because we live and work in a country that isn’t the United States. Aside from French friends, colleagues and neighbors, our streets and offices are dotted with Algerians and Turks and Pakistanis…

We have had our metro and RER shattered by terrorist attacks. Our garbage cans are bolted shut. And our train stations echo with the voice of loudspeaker warnings. As rubble is being cleared and pained relatives are still searching for loved ones, it may still be too painful and certainly too inflammatory to really explore the origins of hatred directed at us, but we must edge quickly to the deeper “why” if we hope to emerge into a safer world. As clearly as we sense that our first concerns are with the victims, a nasty truth lurks right behind — all forms of deliberate violence are rooted to causes. We now share a unanimity that living in fear of targeted attacks is intolerable and must be remedied. But, we must also channel our new commitment to safety into radically different ways of participating in a progressively more secure world. Investing in new ideas as unpopular as they are. That, for me, is patriotism.