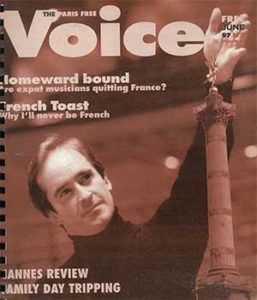

The Paris Opera on the Place de la Bastille is nearly as famous for political strife as the Bastille itself was. The high-tech, 2,700-seat opera house, opened in 1989 as part of the Mitterrand legacy, has witnessed power politics, frequent strikes and the firing of two music directors. When two years ago the new general director of the Opéra de Paris, Hugues Gall, selected an American, James Conlon, as principal conductor and musical adviser, the French press referred to Conlon as the “brave maestro.” Now, nearing the end of his first season, Conlon has not only managed to sail above the strife but has brought new life to the Opera.

The Paris Opera on the Place de la Bastille is nearly as famous for political strife as the Bastille itself was. The high-tech, 2,700-seat opera house, opened in 1989 as part of the Mitterrand legacy, has witnessed power politics, frequent strikes and the firing of two music directors. When two years ago the new general director of the Opéra de Paris, Hugues Gall, selected an American, James Conlon, as principal conductor and musical adviser, the French press referred to Conlon as the “brave maestro.” Now, nearing the end of his first season, Conlon has not only managed to sail above the strife but has brought new life to the Opera.

Conlon continues to be the general music director for the Orchestra and Opera of Cologne Germany, and runs a choral festival in Cincinnati. He also guest-conducts in the US with major symphonic orchestras such as the New York Philharmonic and the Boston Symphony, (with which he is to appear this summer). We caught up with him for this interview last month at the Paris Opera, where he conducted a stunning performance of Wagner’s “Lohengrin” to a standing-room-only house.

Q: With all the xenophobia in France right now, are you ever criticized for occupying such a key position in a musical institution, as an American?

JC: The short and the long answer is no. I have a long history with France. I’ve been a guest conductor here since 1980 [conducting the Orchestre de Paris and then the Orchestre National de France]. I’ve visited France regularly since 1971. I have spent more time in Europe than in the States since 1980. I’m not perceived as an American who just got off the plane. I have a long relationship with French culture. The French appreciate it when they’re appreciated. Nobody’s made an issue of it. If you have a certain reputation, people stop making an issue after a while. At first they said, “He’s an American.” It’s not a gift to be an American. You have to prove yourself.

Q: Do you bring a certain Americanness to your conducting?

A: I hate nationalistic terms. It’s provincialism. I’m not talking about being proud of your culture. It’s collective egoism – instead of saying, I’m better than you, it’s my country that’s better. I love America, I have a lot of roots there. But I’ve traveled all my life. I’ve been around the world several times. I love traveling and meeting people, and cultural interchange. I’m a big believer in no borders.

Q: Do you ever worry you’ll be forgotten since you’re not on the American scene all the time?

A: I live by the credo that I have to live in direct contact with the music I love and people I love to perform it with. It’s like a religious vocation. Wherever I turn out to be, that’s fine. The irony is, it turns out. If wherever you’re doing something works, the markets will find you. I’ve never looked for a job. People always came to see me.

Q: Is there any special repertoire that works particularly well at the Paris Opera?

A: Paris is an international city. It’s not a provincial audience. People want a little bit of everything. We do it all … Italian, German, French, English music. Some people are Wagner fanatics, for example, and they’re the same everywhere in the world. We feel we are the national opera, and should provide a large, very varied repertory on a permanent basis, like London, New York or any other major city. We have two opera houses: Garnier [the older, much smaller house] is the national pride, and we do baroque music – Rossini, Mozart – there. At Bastille [the modern house] we do “Figaro,” “Carmen” and everything else that requires the space and the state-of-the-art technology we have here that is unbelievable.

Of course, there’s a special appreciation of French music like Debussy’s opera, “Pelléas et Mélisande.” Not everyone loves that opera. I’ve conducted it at Garnier, and it’s a pleasure to see a sold-out audience, to see everyone stay till the very end.

Q: What changes have you made at the Opera?

A: I’ve brought in 20 players so far – all French; 95% of the orchestra is French. There are many impressive young people. I’m very optimistic about the future. You can count on many of these players for 20-25 years.

I feel at home here. I have a Latin soul. I love the Latinness of the French personality. I love the French aesthetic and literary sense, the logic and intelligence. I enjoy working with French orchestras. The way to get good results is to be competent and be clear about what you want [and] to show a genuine appreciation for their Frenchness. I genuinely have that for France.

Q: Why did you come to work in Europe?

A: I’m a New Yorker who had never been out of New York till the age of 18, when I went to Aspen to learn conducting. At 20 I went to Spoleto to be an assistant conductor, then backpacking. I had been a provincial New Yorker. Then my attitude changed. I got off the plane in Europe and felt I had found my roots. I had one of those experiences people talk about. I believe that what you are is defined by your family and your environment. It’s where you start. What you become is up to you. It’s about learning other languages, which give you a different way of thinking. You can compare views, challenge your own viewpoints. If I can’t see the old churches and cathedrals I miss it. It’s the greater sense of the passage of time and a historical perspective, the deep, old sense of art. Many American cities have marvelous museums, but you don’t have to go to a museum here, you just walk down the street and the culture is etched in.

Q: What do you like most about Paris?

A: The beauty of the city. It’s not a natural beauty. It’s culture, what has been created. It’s the most beautiful capital in the world. I love the way it looks … the architecture, museums and avenues. It’s the fact that there have been centuries of people demanding that aesthetics of beauty be taken into account into their environment. Some cultures don’t care. Paris is a city that by the grace of God has not been destroyed. Most major cities have been, like London, St. Petersburg, of course the German cities, and that’s their tragedy for their mistakes. Paris has survived. With it you see a spirit, that aesthetic sense that has dominated it and that almost no other major city I’ve ever seen has.

Q: Anything you hate here?

A: The air.

Q: How do you adjust to the different local environments for the orchestras you conduct here and in other countries?

A: I’m willing to open myself to the “other” with a capital O. You have to have your spiritual center. Then you can be open to others and their spiritual centers. It makes you flexible in adapting to what’s around you. You have to surrender your own personality to the spirit of the composition and the composer. You have to have openness, receptivity, flexibility, the ability to listen. It’s a viewpoint, a spiritual, philosophical approach to life.

Q: What future do you see for opera?

A: The question is whether the operatic form fits in with modernity. Maybe we’ll have to wait till the 21st century to have new operas. I don’t know the answer as to what exactly opera will be. Will people still get up and sing with an orchestra in costume in the next century? Opera in the 19th century was like cinema today. People were eager to see the latest opera. Bach and other composers of the past continue to fascinate us. It’s obvious that these works have something that people are drawn to. I don’t have a problem performing things written a long time ago. I have no shame of loving and devoting my life to it. You have to keep representing it with honesty and dedication.

Q: After conducting and recording the music for the film “Madame Butterfly” [produced by Frédéric Mitterrand,] you said you wanted people with no musical connection to be able to share the experience. How is this possible?

A: We have the hope that there’ll be more movies about opera. Look at the impact “Shine” made on people who weren’t involved in music. I feel we are sharing programs of classical music. But we are a minority group compared to Hollywood or rock music.

There are programs at the Opera for kids from underprivileged areas, from the age of 8 up all the way to students in their 20s. We take them on tours of the opera houses, they see us work, that you don’t have to be a snob to love opera. The veneer of elitism has worked against classical music. But fortunately things have changed. An opera house should be user-friendly.

Q: Are you worried about the audience getting older?

A: There’s no question that we worry about graying audiences. My goal is not only that we don’t lose the audience we have, but I want a lot more people to listen to classical music. My fantasy is that everyone would listen to classical music. It’s not probable, but it is possible. I believe education happens on the radio. People learn to love music that way, not in schools. What if people heard classical music on their Walkmans, in elevators? If it were Mozart and Brahms, they’d love it like they do rock music.

Q: You lead an extremely fast-paced life, juggling orchestras, opera houses, recording sessions, master classes and countries. What’s the hardest thing about it?

A: Jet lag, especially from the US to Europe. I avoid it as much as possible. I have a very strong constitution. People are horrified at my schedule. I believe deeply that if you’re doing what you love to do, you have energy you don’t have when you’re doing what you hate. I live a life of discipline. I believe in discipline. In a sense, my life is not my own. That’s how it is. I love it, I live for this, this is my life.